Effects of a Mobile-Based Vocational Skill Building Coaching Technology Intervention for People with Cognitive Disabilities: a pilot feasibility study

Patricia Heyn, PhD1, Aleaza Goldberg, MA1, Mike Melonis, BS1, Sarel Van Vuuren, PhD2 and Cathy Bodine, PhD1

1 Assistive Technology Partners, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus

2University of Colorado, Boulder

The most common difficulties that individuals with cognitive disabilities experience are 1) difficulty remembering the sequence of what to do, 2) remembering what they should do next, and 3) loss of the context of their current activity. For occupational activities that require independence and mobility such as custodial, mail delivery, grounds maintenance, and assembly warehouse errands, the inability to maintain context and task sequence is the primary barrier to many individuals affected by cognitive impairments to be productive and to have a safe and enjoyable work environment. Therefore, we designed a Mobile Coach Technology (MCT) aimed to support individuals with cognitive disabilities in performing assembly job tasks that involves mobility/navigation. The MCT was designed to be used with smart technologies such as iPads, tablets, and smart phones. It provides context verbal prompting to assist individuals to complete the steps involved in the job tasks. It also poses questions to the workers relevant to their work to help them to maintain the necessary engagement and context to complete the job successfully.

BACKGROUND

Technology trends and current demographic changes support the development of web and mobile applications. As of April 2009, more than 63% of Americans had broadband access, increasing by 15% from the previous year1. More than 32% had used a cell-phone or smart phone for emailing, instant-messaging or information-seeking, up 33% from the previous year, with 19% of Americans using the Internet on a mobile device on a typical day2. Supporting this trend, the Apple mobile App Store had more than one billion application downloads in its first 9 month3. Within this context, the benefits, ease of access and ubiquity of online and mobile solutions make them attractive platforms for delivering assistance to individuals with cognitive disabilities4,5. In the battle between the PDAs and mobile phones, Smartphones won out, eroding the market for PDAs. A similar battle is quietly brewing between the mobile phone and PC companies for a new class of emerging low-power mobile lifestyle devices called Mobile Internet Devices (MIDs).

In general, a Mobile Internet Device (MID) is defined as a multimedia-capable handheld computer providing wireless Internet access6. They are usually designed to provide entertainment, information, and location-based services for personal use, rather than for corporate use. MIDs are larger than smartphones but smaller than the Ultra Mobile PC (UMPC). They have been described as filling the gap between smartphones and Tablet PCs6. It allows two-way sharing through the cellular network. A new generation of MID allows people to have great mobile performance, wireless connectivity, communicate with others, and stay informed.

For a handheld device, MIDs have an unprecedented level of multimedia capabilities and typically come in a tablet-like form factor. MIDs are not designed to replace mobile phones (or Smartphones) but to be used as companion devices 2 especially to individuals who are affected by physical and mental frailty5.

Preliminary Studies

This study is part of a series of development and research projects from the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center Grant for the Advancement of Cognitive Technologies (RERC-ACT)7. Handheld devices with these capabilities represent an opportunity to assist people with cognitive disabilities to use mobile technology that can be easily accessible for any circumstance that the user might needs4,5. Our previous development project, Mobile Skills Vocational Coach Device (RERC-ACT D4 Project)7, was based on designing and testing a series of iterative design research processes prior to this study7. We have also tested two different prompting system technologies for persons with cognitive disabilities (Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board #09-1210). The previous prototype device model functioned well and met the development and research requirements for further investigations, which has advanced to the feasibility study proposed here. This study is approved by the University of Colorado institutional review board (COMIRB #13-3202).

Therefore, we are now reporting the results of the feasibility pilot study that used an ecological approach to evaluate a “Mobile-Based Skills Build Coach Technology” (aka Mobile Coach Technology) for working age adults with Cognitive Disabilities (CDs).

PURPOSE

The purpose of this feasibility study is to evaluate a Mobile Coach technology in an ecological environment (warehouse) that employed adults with significant cognitive impairments as defined by pre-established cognitive disability per Department of Education (DoE) criteria for Significantly Limited Intellectual Capacity (SLIC). The study was designed to address the following hypothesis:

Working adults with cognitive disabilities who used the Mobile Coach (MC) technology (iPad system) will show higher satisfaction in performing the selected working assembly tasks (i.e. easier, better to do the task) as compared to the standard working group (no MC technology).

METHOD

Subjects

Working age individuals from a community employment program, aged 18-64, who meet the criteria for Significantly Limited Intellectual Capacity (SLIC) as defined by the Colorado DoE were invited to participate on a “one-time only” testing section (cross-sectional) of a technology-based mobile context-aware prompting system (CAP) designed to coach/train and aid individuals with cognitive impairments in performing assembly tasks.

These individuals also meet the criteria for developmental disabilities services eligibility in Colorado15 per the Division for Developmental Disabilities Office of Adult, Disability and Rehabilitation Services at the Colorado Department of Human Services. These criteria mandate that the individual must have significant cognitive impairments and adaptive functional skills that place them at or below one percentile of the general population (Colorado Association of Community Centered Boards, 2013)16. For the purpose of this study, participants were only included in the study if they could express some sort of communication, either orally or by using a communication device.

Intervention

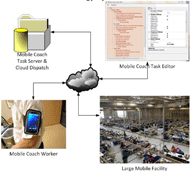

The intervention was based on one four hours session (Mobile Coach Technology or Standard Vocational Coach) of a technology-based mobile context-aware prompting system (CAP) designed to job coach/train and aid work performance for adults with significant cognitive impairments (figure 1). Each enrolled participant was placed to either the Mobile Coach Technology Intervention (iPad technology) or to the Standard Vocational Intervention (coached by a human). Both groups were exposed to similar procedures while performing the assembly task job. However, one group had the assistance of a virtual agent (Mobile Coach Technology on the iPad) and the group of a human job coach (without technology).

Instrumentation

Work Environment

The Mobile Coach Project team worked in collaboration with a Community Integrated Employment and Supported Living Services program that served Century Link in packaging the residential telecommunication equipment (e.g. DSL modem). This service was performed by individuals with cognitive disabilities who worked on repackaging the Century Link pallets. Depending on the type of residential telecommunication equipment, each pallet contained 12-24 cases and each case contained 10-14 residential devices. Once delivered, these pallets were temporarily stored in the warehouse.

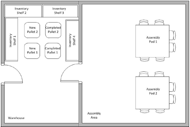

The physical layout closely resembles Figure 2. The warehouse and the assembly area are adjoining rooms. The approximate distance from the pallets to the assembly pods range between 50- 100 feet.

Procedures

Each worker from the community employment program had the opportunity to volunteer or decline participation in the study. Consenting procedures were performed for each subject and their understanding about the study was evaluated by asking specific questions about the study after consenting explanation such as “what is this study about?” or “ if you agree to participate what do you think that you will do in this study?”. Demographical information was obtained from each participant. Enrolled participants’ level of comprehension and understanding was acquired by using the Mini Mental State Exam8.

Intervention

The job performed by the mobile worker included six high level tasks:

- Unwrap new pallet;

- Get new case/box;

- Deliver new case/box to assembler (mobile task);

- Retrieve completed case/box from assembler;

- Place completed case/box on pallet in the storage room (mobile task);

- Secure completed pallet.

Each of these tasks required one or more prompts to complete the task. The overall sets of prompting were a collection of sequential steps and dual path decision points. Sequential steps were incremented either via a timer event expiring or a gesture performed by the user on the IPad (Mobile Coach Technology). All decision points required the user to perform the correct gesture.

Data Collection

A project specific survey was designed to evaluate participant’s satisfaction with the intervention. The survey has 14 questions related to their experience with the coaching intervention with a response level of 1 to 5 where 1 and 2 means “Not at all”, 3 and 4 means “Somewhat” and 5 means “Very Much”. The scale was designed to ask similar questions for both groups (MC Technology and no MC Technology).

RESULTS

A total of 19 workers (5 females and 14 males) with cognitive disabilities were recruited and consented into the trial. Sixteen participants passed inclusion criteria (physical ability to manipulate assembly work tasks) and were enrolled in the intervention. Three participants were excluded because of mobility limitations (wheelchair or walker user). Participants’ disabilities ranged from a variety of cognitive impairments (i.e. Down syndrome, Autism, and Brain Injury). The sample comprised of 65% white, 20% Hispanics and 15% African Americans.

At the end of each trial participants were asked to provide feedback related to the usability and supportive assistance level of the two job coach format. The MC technology group reported higher satisfaction with the intervention as compared to the no MC technology group. Approximately 80% of the MC technology responses collapsed into the “Very Much” reporting level category on questions related to “enjoyment doing the work”, “work was easy”, “the work was easy to remember”, “was easy to use and understand the MC technology”, “the MC technology help you do your job better”, “did the screen help you do your job better” as well as questions related to adherence just as “would like to use the MC technology again?”.

The standard group (no MC technology) also expressed positive satisfaction in having job coach assistance while performing their tasks; however their response levels fall one to two scores below the higher score as compared to the MC group. 70% responded “somewhat” to “very much” satisfaction with the human-based job coach.

The results of the study indicate that there were differences in the responses between groups and the integration of a Mobile Coach technology was well-received by the workers. Most of the participants were extremely excited and eager in participating in the study and they wanted to use the technology. To accommodate their desire to experience the technology, we provided time to “play” with the technology for the group that was not assigned to the MC technology when they completed the experimental procedures. There were no differences between the participants who were already used to use computers or iPads versus those with no previous experience. In addition, 25% of the sample was illiterate and literacy levels did not influence their performance when using the technology. Although this area was not formally studied, self-report by some of the subjects could be impacted by their level of cognitive status.

DISCUSSION

The Mobile Internet Devices (MIDs) technologies have improved over the years and are more affordable and easily available than years ago. Smart technologies, such as Smartphones, are leading the market for mobile technologies and can be considered flawless assistive technology devices for individuals with cognitive impairments. Presently this technology is so easy to use that it can be manipulated by touch or voice command. The prospective for positive impact for individuals with disabilities, ease of access and use of the mobile solution technologies make them an attractive platform to assist individuals with cognitive impairments in performing tasks that require prompting assistance such as assembly job activities.

The results of this study supports the notion that these technologies and programs that can be easily adapted for its use will grow exponentially to a more effective, easily available and integrated system to meet the occupational needs of individuals with cognitive disabilities.

Study Limitations

Although, as part of the experiment, we collected data on the technology function, the Mobile Coach Technology system would sporadically have mal functions during the experiment. However, this only occurred with some trials and only for some subjects and it was carefully recorded. After the system was restored and functioning, the timer and data collection system was re-started and the trial was resumed. The short time in using the mobile coach technology was also a limitation. We could have learned additional information if workers were exposed longer to the system. Another limitation of the study was the ecological environment. Since the intention of the study was to test the technology in a real world setting, we had to deal with the non-controllable factors that a real working warehouse presents such as constant loud noise and other unexpected distractors. We also faced the absence of materials to complete the work such as the lack of cases/pallets. At many occurrences we had to cancel a planned visit due to the absence of pallets that were not delivered at the warehouse at the designated date. In addition, we had to deal with continuous stops during the experiment due to breaks and lunch time. The small sample size also limits the generalizability of the results. Another major limitation was that we did not include the facility vocational training coaches into the study procedures. After the study implementation phase, we learned that the vocational coaches could have been important participants in the study as to give us feedback about the system such as usability of the program accordingly to the workers ability and job tasks, practical adaptation of the system into their program and routine, and technology features feedback.

CONCLUSION

The results of this feasibility study that evaluates a mobile coach technology has translational and pragmatic implications, particularly for settings that employee and provide vocational training for individuals with cognitive disabilities. The aim of the study was to test the system with workers with cognitive disabilities in a real job training situation. The study main outcome was user satisfaction and feasibility of such technology in an ecological work environment. The results showed that such system has the potential to assist and impact positively the vocational training and performance of workers with cognitive disabilities who are involved in tasks that require memorizing steps that require a well-ordered action in adjunction to spatial recognition abilities.

It is important to note that the program has great potential for commercialization and knowledge transfer. The Mobile coach program could be designed into “apps” or similar platform for mobile technologies.

This study was undertaken in an attempt to compare a mobile coach technology versus a human coach. Although several limitations impacted the study’s generalizability such as the small sample size, we were able to recruit a well-balanced heterogeneous sample for groups for comparisons. In addition due to the ecological element of the study, we used mix-methods appraisals (qualitative and quantitative) to evaluate the groups’ performance. Therefore, further research is recommended to evaluate in a larger sample with a longer duration experimental design the features and effects of the Mobile Coach Technology for workers with cognitive disabilities.

REFERENCES

- Horrigan, J. Wireless Internet Usage 2009. Washington, D.C: Pew Internet & American Life Project an initiative of the Pew Research Center. [cited 2015 January]; Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2009/07/22/wireless-internet-use/

- Horrigan, J. Home Broadband Adoption 2013. Washington, D. C.-Pew Internet & American Life Project an initiative of the Pew Research Center. [cited 2015 January]; Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/08/26/home-broadband-2013/

- Apple: `Over 1 billion downloads in just nine months' 2009 [cited 2009 July 28, 2009]; Available from: http://www.apple.com/itunes/billion-app-countdown

- Carey, A. C., Friedman, M. G., & Bryen, D. N. (2005). Use of electronic technologies by people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation, 43(5), 322-333.

- Pew, R., Hemel, S. V., Technology for Adaptive Aging. 2004, Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- The state of mobile back end as a service. December 2014 [cited 2015 January]; Available from: http://www.computerweekly.com/feature/The-state-of-mobile-back-end-as-a-service

- Heyn PC, Cassidy JL, Bodine C. (2014) The Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center for the Advancement of Cognitive Technologies. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen.

- Folstein, M., Folstein, S., & McHugh, P. (1975). “Mini-mental state”: A practical for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189-198.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by funding provided by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) Grant #H133E090003 and the Coleman Institute for Cognitive Disabilities.