Impact of Tilt-in-Space Power Wheelchairs on Health, Activity, and Participation

Frances Harris, PhD; Sharon Eve Sonenblum, ScM; Stephen Sprigle, PhD, PT, Christine Maurer, PT

ABSTRACT

This paper reports the results of a pre-post outcomes study on the impact of tilt-in-space power wheelchairs on the health, activity, and participation of 5 subjects. Using a methodology which combines traditional self-reports and activity monitoring technology, subjects who had previously used an upright power wheelchair were monitored at baseline and 3 months following receipt of a new tilt-in-space power wheelchair. Subjects visited similar numbers of destinations pre and post. However, wheelchair use metrics - including occupancy time, distance wheeled, and number of bouts - varied pre and post, without a consistent direction of change. Quality of life measured as self-perceived health status increased in all subjects. Although subject population is too small to generalize results, this study illustrates the complexity of participation measurement and the utility of this methodology to provide insights into the relationship between wheelchair use and activity and participation.

KEYWORDS:

wheeled mobility; activity and participation; outcomes

BACKGROUND

The measurement of activity and participation has emerged in recent years as a key area of outcomes research (1-5). In addition, recent advances in wheelchair and seating technology provide wheelchair users with greater equipment options such as tilt-in-space, standing, and reclining functions. These new technologies are often touted for their medical and functional benefits, however, their benefits have not been adequately studied and remain unsubstantiated, making reimbursement more difficult to justify. To this end, we measured wheelchair use, health, activity and participants in a small cohort of full-time wheelchair users in order to identify changes following a clinical intervention in which they received a new tilt-in-space power wheelchair.

There are numerous problems associated with the measurement of participation among wheeled mobility users (6). In particular, self report measures are inconsistent in how assistive technology (AT) is assessed and scored (7,8). A methodology – the Wheelchair Activity Monitoring Instrument (WhAMI) – was developed at the Center for Assistive Technology and Environmental Access (CATEA) at the Georgia Institute of Technology to passively gather objective data about peoples’ mobility activities in their homes and communities (9,10).

METHODOLOGY

Research conducted at CATEA and Shepherd Center between 2004 and 2006 examined wheelchair use, community activity, and health among 5 subjects, once in their current power wheelchair and again 3 months following receipt of their tilt-in-space power wheelchairs. Three months was thought to be an adequate length of time to allow subjects to accustom themselves to their new wheelchair. Subjects completed a health questionnaire and a self-assessment of health status (SF-8) (11). Subjects’ wheelchairs were instrumented with the WhAMI for a two-week period which measured wheelchair occupancy, wheel revolutions, and global position. Wheel revolutions are reported in terms of average distance and number of bouts wheeled daily. As reported elsewhere, bouts generally tend to serve as transitions between stationary activities (10,12). In some cases, however, longer bouts may reflect the activity itself. A prompted recall interview (PRI) was administered within 48 to 72 hours after chairs were de-instrumented to administer a PRI in order to determine the activity purpose at recorded destinations, subjects’ mode of travel, and travel companions.

RESULTS

Data were collected from 5 experienced wheelchair users (1 male and 4 female). Subjects’ ages ranged from 36 to 60. Diagnoses included spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, dystonia, multiple sclerosis, and muscular dystrophy. Reasons for prescription of the tilt feature included pressure reliefs and pressure sore prevention, increased postural stability, positioning and comfort. All subjects signed an informed consent form.

Wheelchair use varied between pre and post assessments for all subjects (Table 1). Changes to wheelchair occupancy between assessments were present for all 3 subjects for whom we have data, but no trend was evident. Distances wheeled increased in 3 of 5 subjects after receiving their new wheelchair. In contrast, Subject B wheeled a shorter distance after receipt of her new wheelchair. Subject B’s significant decrease in wheeled distance did not, however, correspond to a large decrease in bouts of mobility.

|

Subject |

Occupancy Time (hours) |

Distance Wheeled (m) |

# Bouts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

|

A |

11.9 |

10.2 |

1247 |

1439 |

212 |

189 |

B |

n/a |

15.7 |

3795 |

1395 |

119 |

106 |

C |

n/a |

12.6 |

999 |

1188 |

69 |

102 |

D |

11.6 |

12.5 |

571 |

319 |

140 |

82 |

E |

13.9 |

11.4 |

776 |

1151 |

100 |

133 |

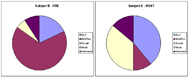

Figure 2: Breakdown of activity type or destination purpose for Subject B. DLT = daily living task; Ent/Rec = Entertainment, recreation or leisure. (Click for larger view)

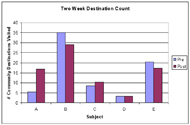

Figure 2: Breakdown of activity type or destination purpose for Subject B. DLT = daily living task; Ent/Rec = Entertainment, recreation or leisure. (Click for larger view) The number of community destinations visited over the 2 week instrumentation period ranged from 3 to 29 (Figure 1). However, for 4 of 5 subjects there was little difference in number of destinations within subjects between baseline and post assessments. For one subject (B), the distribution of activity type (or purpose for destination) did change between pre and post assessments (Figure 2.)

Unlike the variability seen in measures of wheelchair use and activity, health (measured as both physical and mental health) improved during the post assessment as compared with pre (Table 2). Three subjects demonstrated improvements in both their physical and mental scores while the remaining two subjects showed improvements in only one of the two categories.

Physical Score |

Mental Score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pre |

Post |

Change |

Pre |

Post |

Change |

|

A |

48.62 |

33.52 |

-15.10 |

54.50 |

48.51 |

-5.99 |

B |

60.74 |

56.90 |

-3.84 |

54.14 |

54.09 |

-0.05 |

C |

33.21 |

38.13 |

4.92 |

48.37 |

43.38 |

-4.98 |

D |

32.62 |

30.94 |

-1.68 |

29.24 |

27.65 |

-1.59 |

E |

32.87 |

32.72 |

-0.15 |

51.95 |

54.51 |

2.55 |

DISCUSSION

The small sample size of this study prevents generalization of results. However, the following observations were noted during the prompted recall interview:

- Significant changes to three subjects’ occupancy time reflected situations other than the wheelchair. For example, during the baseline assessment PRI Subject E said she acquired a reclining easy chair. Her chronic pain and discomfort were relieved by switching between the two chairs during the day, resulting in less wheelchair occupancy time in her post assessment. In another case, Subject A was ill during the first week of instrumentation during her post assessment, resulting in lower occupancy time. Lastly, Subject D’s increased pain and the relief provided by her new wheelchair resulted in slightly higher occupancy time.

- In almost all cases, subject’s occupancy times were greater than the median subject from a larger study (n=20, 10.6 hours) and represented a significant portion of the day (12). This is consistent with subjects’ reliance on their wheelchair for mobility activities.

Interpretation of changes in wheeled distance was contextualized during the PRI. Although wheeled distances increased in 3 out of 5 subjects, there was one notable exception. Subject B’s data showed a large (>60%) decrease in wheeled distance, but not a corresponding decrease in bouts. The PRI revealed that the colder weather in her post assessment in January impacted both her wheelchair use and mode of travel compared to her baseline assessment in June. In June she wheeled 68% of her distance outdoors, mostly around her neighborhood for recreational purposes. In January she wheeled less and relied more on her van for daily living tasks, such as visiting grocery stores. However, during both assessments, the majority of the distance wheeled was in the community, while the largest percentage of bouts continued to be wheeled in the home. Homes tend to contain small, purposeful spaces (e.g., kitchen) in which key daily activities occur and frequency of bouts, as reflecting transitions between activities, is less likely to be affected by changes in the external environment.

Stability of destinations in all but one subject suggests that, as experienced wheelchair users, the change from a power to a power tilt-in-space wheelchair did not significantly impact the frequency of community activities.

Overall, the improved health outcomes as measured with the SF-8 suggested an overall positive impact of their new wheelchairs. However, results were not directly correlated with change in either number or type of community activities, nor in their wheelchair use metrics.

CONCLUSION

Although this study’s subject number was too small to generalize results, the relationship between wheelchair use metrics and activity and participation, as assessed by frequency and type of activity, reflect the complexity of participation measurement. Continued research is needed to determine trends and patterns of wheelchair use and participation in activities. Nonetheless, this methodology offers the potential to query complex mobility patterns and activities among people who rely on wheeled mobility devices or who may use a variety of mobility aids. By providing valuable normative data about wheelchair use and activity WhAMI can point to potential outcome variables (such as self-perceived health status) that may inform future studies. In addition, by capturing objectively-derived mobility and activity data, clinicians can compare client perceptions of wheelchair use and functional performance in the clinic against data derived from wheelchair use in the everyday environment.

REFERENCES

- Fuhrer MJ, Jutai J, Scherer MJ, DeRuyter F. A Framework for the Conceptual Modelling of Assistive Technology Device Outcomes. Disability and Rehabilitation 2003;25(22):1243-1251.

- Gray D, Hendershot G. The ICIDH-2: Developments for a New Era of Outcomes Research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81(2):S10-S14.

- Jette A, Haley S, Kooyoomjian J. Are the ICF Activity and Participation Dimensions Distinct? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2003;35:145-149.

- Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Post M, Asano M. Participation after Spinal Cord Injury: The Evolution of Conceptualization and Measurement. Journal of Neurological Physical Therapy 2005;29(3):147-156.

- WHO. ICF: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2001.

- Harris FH. Conceptual Issues in the Measurement of Participation Among Wheeled Mobility Device Users. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2007 2(3):137-148.

- Rust KL, Smith RO. Assistive Technology in the Measurement of Rehabilitation and Health Outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005;84:780-793.

- Smith RO, Jansen C, Seitz J, Rust KL. The ICF in the Context of Assistive Technology (AT) Interventions and Outcome. ATOMS Project Technical Report. http://www.r2d2.uwm.edu/atoms/archive/icf.html 2006.

- Lankton S, Sonenblum S, Sprigle S, Wolf J, Oliveira M. Use of GPS and Sensor-based Instrumentation as a Supplement to Self-Report in Studies of Activity and Participation. 2004; Atlanta, GA.

- Sonenblum S, Sprigle S, Maurer C. Monitoring Power Upright and Tilt-In-Space Wheelchair Use. 2006; Atlanta, GA.

- Turner-Bowker D, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8™ Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Quality of Life Research 2003;12(8).

- Sonenblum SE, Sprigle S, Harris FH, Maurer CL. Characterization of Power Wheelchair Use in the Home and Community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;accepted for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding was provided by the RERC on Wheeled Mobility funded through NIDRR (H133E030035). We would also like to thank Patricia Griffiths, PhD for her help in statistical interpretation.

Contact Information:

Frances Harris, PhD

Center for Assistive Technology & Environmental Access

Georgia Institute of Technology

490 Tenth St., NW

Atlanta, GA 30332-0156

914-945-7005

914-945-7031

frances.harris@coa.gatech.edu