Effects of Educational Intervention on use of Tilt-in-Space

Penny J Powers, PT, MS, ATPa, Ashley Barrettb, Leigha Cuellarb, Meagan Heneyb, Martha Schumpertb, Renee Brown, PT, PhDb

aPi Beta Phi Rehabilitation Institute, Adult Seating and Mobility Clinic, Vanderbilt University

Medical Center bSchool of Physical Therapy, Belmont University

INTRODUCTION

There are wide variations in reported use of wheeled mobility in the United States. According to the University of California–Disability Statistics Center (2013), an estimated 1.7 million individuals in the United States use a wheelchair. The Americans With Disabilities: 2005 reported that 3.3 million people use a wheelchair or similar device.1 Many of these individuals have limitations in their ability to reposition themselves for postural control during functional activities and for pressure relief, placing them at risk for development of many multi-system health complications. Mobility limitations can also affect motivation to interact outside the home environment exacerbating one’s state of disability.2 Social participation is an important marker in consideration of quality of life and the ability of the appropriate seating device to facilitate environmental interaction must not be ignored.3 The central goal of seating device prescription is to minimize disability by maximizing functional independence and interaction.

Patient-centered evaluation of functional outcomes for individuals who use wheeled mobility full-time is critical to assure proper fit and minimize risks/limitation due to inappropriate or no longer adequate fit which can lead to pressure ulcers, pain, poor posture, poor circulation, edema, gastrointestinal problems, difficulty breathing and swallowing, and secondary neurologic problems due to prolonged compression.4 In addition, Dicianno and colleagues reported several specific medical purposes (orthostatic hypotension, pathologic tone, autonomic dysreflexia, bowel and bladder management program compliance, orthopedic deformity) for which the best clinical management is training patients to use combinations of wheelchair features tilt, recline, and leg rest elevation.5

Tilt-in-space (TIS) is one of the features often prescribed for individuals with limited mobility in order to provide pressure relief and afford greater external postural control. This feature allows the seat-to-back angle to remain fixed while the whole chair is tilted with respect to the ground, shifting body weight from posterior thighs and ischial tuberosities to the back. LaCoste and colleagues reported that 57% of subjects using prescribed power chairs considered the tilt feature essential for ADLs including reach of objects, sidewalk access, and hygiene practices.6

Evidence in the literature suggests that pressure at the ischial tuberosities is reduced 27 - 47% when TIS was observed at 35˚ and 65˚ respectively.7 LaCoste et al. also found that tilt greater than 30˚ is recommended for achieving an effective weight shift, but results showed that more than 50% of subjects assumed a tilt angle smaller than that which affords a true weight redistribution. Tilt angles of less than 20˚ were more often occupied.6 Sonenblum et al. assessed the nature of tilt-feature use in power wheelchair users in 2006 who tilt to at least a 15˚ angle 16 +10 times per day; the subjects spent an average of 28 minutes at >40˚ tilt daily.8 In a later study in 2010, Sonenblum and Sprigle found that pressure measured at ischial tuberosities was not diminished at 15˚ of tilt, but a pressure reduction was demonstrated at angles of tilt >30˚.9

Despite the documented benefits of optimal angle, tilt duration and frequency are still not well defined. Dicianno et al. referenced a study reporting that the lift achieved during wheelchair push-ups needed to be at least 2 minutes in duration “in order to return tissues to unloaded levels”.5 Researchers recognized this as an absolutely unreasonable expectation even for patients with capable, healthy upper extremity joints and function, promoting repetitive overuse injury. For many full-time wheelchair users, especially those with hemiplegia, cervical spinal cord injury, motor neuron loss affecting postural musculature and upper extremities, these push-ups simply are not an option. This RESNA report estimated that 30 seconds every 15-30 minutes may be a helpful guideline for tilt duration/frequency.

With a growing body of evidence supporting tilt, clinicians must also advocate with payers for reimbursement, as individualized seating and mobility prescription is costly. Mortenson and colleagues reported in 2007 that wheelchair prescription easily exceeded $10,000.10 Certainly, many patients are not prepared for such out-of-pocket costs. Documenting patient outcomes and communicating evidence to funding agencies is an important step in the process of substantiating coverage for power chair features.11 As Dicianno et al. reported, tilt, recline, and other chair features are each used for specific medical purposes, and sometimes in combination depending on the unique needs of the patient.5 Tilt, specifically, was cited as being particularly essential in the clinical management of postural dysfunction and misalignment, spasticity, blood flow, pressure relief for full-time wheelchair users.5 Tilt in combination with either recline or legrest elevation was indicated for better management of pain/fatigue, edema, orthopedic deformities, bowel and bladder management, tendency for skin breakdown with transfers, visual orientation, speech, respiration, and digestion.5 This evidence supports coverage of prescribed features and can help clinicians advocate for patients individual needs.

As previously cited, patients do not always use the features of their seating/mobility system adequately for minimizing development of secondary complications. Dicianno suggested that with the current evidence in the literature concerning inadequate use of tilt for optimal benefits, biofeedback training and follow-up are essential components of the seating prescription.

The purpose of this study was to determine if a targeted educational intervention would improve patients’ ability to consistently tilt their chair to therapeutic angles for pressure relief, reduced pain, and increased functional mobility as measured by pain and tilt surveys, and completion of the Functional Mobility Assessment.

METHODS

Participants

Fifteen adult subjects were recruited from the Adult Seating and Mobility Clinic and Vanderbilt’s MDA/ALS Clinic. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Belmont University. All subjects from the Adult Seating and Mobility Clinic were recruited at the fit appointment when they received their new power-seating device with the tilt-in-space feature. Participants from Vanderbilt’s MDA/ALS Clinic were recruited if they had current means of power mobility with tilt-in-space. Subjects were eligible if they were independent in controlling their power chair and had the ability to communicate via verbal or augmentative means. If a subject was placed in the experimental group, he/she must have been able to return to the clinic one month after the fit for re-evaluation.

The experimental group consisted of six participants with diagnoses of spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS), and cerebral palsy (CP). This group received an educational program on tilt-in-space. Nine participants were in the control group and had diagnoses of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or MS. These participants had previously received a chair with tilt feature. They had received “usual and customary” instruction for the use of tilt when they received their current seating and mobility device.

Procedure

All subjects recruited were asked to rate their pain levels when upright and their usual tilt position on a scale from 0-10 using the Wong-Baker faces. The Functional Mobility Assessment (FMA) was also administered via interview.11 The FMA is an outcome tool that measures a patient’s agreement/disagreement regarding their functionality in their power chair. There are ten statements, which include ability to perform ADLs, comfort, health concerns, transfers, indoor/outdoor mobility, and accessibility to public and private transportation. The control group was given a tilt survey which included questions regarding how often he/she used the chair and the TIS. The subjects were then asked to tilt to their usual position and the degree of tilt was measured with an inclinometer and repeated three times. The experimental group received additional verbal education regarding the benefits of tilt, demonstration /practice with a light that turned on at 30˚ of tilt, a picture of them appropriately tilted, an educational handout and check-off sheet. They were then asked to return to the clinic in one month. Upon return, they were asked to rate their pain (upright and tilted), complete the FMA and the tilt survey, including tilt measurements. The experimental group was offered the educational module after their final data was collected.

RESULTS

Average tilt was compared using independent samples T-tests. The FMA scores were analyzed using the Mann Whitney U Test.

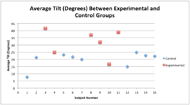

Tilt Degrees:

Figure 1

Figure 1

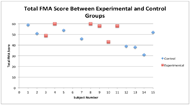

FMA:

Figure 2

Figure 2

Pain Survey:

The majority of subjects reported no pain or minimal pain in their chairs, both upright and tilted.

Tilt Survey:

The tilt survey provided information based on patient report. Two of the subjects from the control group reported pressure ulcers related to their chair use within the last year. Only two of the subjects reported not using their chairs daily. Ten subjects reported using their chair for >10 hours each day. Fourteen subjects reported using the tilt feature on their chair every day. When asked why subjects tilted, 73% reported tilting due to discomfort and 33% tilted due to pain.

DISCUSSION

The results indicate that a targeted educational program that took approximately 10 minutes to administer was effective in training patients to tilt to greater than 30˚, in the therapeutic range for pressure relief. Two of the control subjects reported the presence of pressure ulcers within the last year. They demonstrated 15˚ and 23˚of tilt, which is below the therapeutic range and may have contributed to the development of ulcers. One of the participating subjects (diagnosed with ALS) shared during her visit that her chair’s tilt feature was important to her because at times she can tell she is sliding down in her seat, but cannot reposition herself on her own; tilting allowed her gravity-assisted repositioning for postural stability and made her feel safer.

All participants received an opportunity to tilt to 30˚ using a temporary light system that was attached to their wheelchair, as a biofeedback tool. The light was set up to turn on once the patient reached 30˚ and, thus, the patient was able to know exactly when they had obtained a therapeutic angle of tilt. This was an extremely useful tool to provide a visual feedback for the subjects for the appropriate degrees of tilt. One subject also timed the length of time that it took for the chair to reach 30˚ so that he could use his cell phone timer to make sure that he was at the appropriate angle at home. The use of technology enhances compliance.

The subjects reported strong agreement with the functional statements on the FMA, indicating that their wheelchair prescription afforded them a high degree of functionality and comfort with their prescribed wheelchair. This was reinforced by the minimal to no pain reported by either group in the pain survey. All the subjects in the control group had progressive neurologic disorders whereas the subjects in the experimental group were a mix of progressive and non-progressive neurologic disorders. This may account for the lower FMA scores in the control group, however there was not a statically significant difference.

CONCLUSION

This study supports that a specifically targeted tilt education program influences patients to utilize tilt within the therapeutic range compared with customary care delivered with power chair prescription. Further research needs to be conducted in developing the visual feedback device for consumer use. In addition, investigation of educational interventions for maximum benefit of tilt in space technology needs to be continued to enable the optimum procedures/education to be included in standards of care.

REFERENCES

1. Brault, M. (2012). Americans with Disabilities: 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administation, 70-131.

2. Hoenig, H., Landerman, L., Shipp, K., George, L. (2003). Activity restriction among wheelchair users. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 1244-51.

3. Evans, S, Frank A, Neophytou C, Souza L. (2007). Older adults’ use of, and satisfaction with, electric powered indoor/outdoor wheelchairs. Age and Ageing, 36, 431-435.

4. Rader, J., Jones, D., Miller, L. (1999). Individualized wheelchair seating: reducing restraints and improving comfort and function. Top Geriatric Rehabilitation, 15(2):34-37.

5. Dicianno, B, Arva J, Betz K, et al. RESNA position on the application of tilt, recline, and elevating legrests for wheelchairs. Assistive Technology: The Official Journal Of RESNA [serial online]. 2009 Spring 2009;21(1):13-22. Available from: MEDLINE Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed October 9, 2014.

6. Lacoste, M., Lambrou, M., Allard, M., Dansereau J. (2003). Powered tilt/recline systems: why and how are they used? Assistive Technology, 15, 58-68.

7. Moes, N. (2007). Variation in Sitting Pressure Distrubution and Location of the Points of Maximum Pressure with Rotation of the Pelvis, Gender, and Body Characteristics. Ergonomics, 50(4), 536-61.

8. Sonenblum, S., Sprigle S., Maurer, C. Monitoring Power Upright and Tilt-In-Space Wheelchair Use: RESNA. 2006. Atlanta, Georgia.

9. Sonenblum, S., Sprigle S. (Eds.). Proceedings from RESNA Annual Conference, 2010: Blood flow and pressure changes that occur with tilt-in-space. Las Vegas, Nevada.

10. Mortenson, W., Miller W., Miller-Pogar J. (2007). Measuring wheelchair intervention outcomes: development of the wheelchair outcome measure. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 2(5): 275-285.

11. Kumar, A., Schmeler, M., Larmarkar, A., Collins, D., Cooper, R., Cooper, R., Shin, H., Holm, M. (2012). Test-retest reliability of the functional mobility assessment (FMA): a pilot study. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1-7.