Visualizing system complexities and diverse stakeholder perspectives: A co-design approach to enhance the wheelchair acquisition and service delivery process

Kahmin Ong1, Elizabeth B-N Sanders1, Yvette Shen1, Theresa Berner1,2, Carmen DiGiovine1,2

1The Ohio State University, 2Assistive Technology Center at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

INTRODUCTION

The wheelchair acquisition and delivery process directly affects individuals with mobility challenges and is often perceived as a standardized procedure primarily overseen by clinical and rehabilitation professionals [1]. However, this process is deeply entwined with complex funding structures, service provision systems, and diverse stakeholder interests, raising critical questions about whether it truly serves the needs of wheelchair users.

In the United States (US), 5.5 million adults rely on wheelchairs for mobility and daily activities, making tailored Complex Rehabilitation Technology (CRT) that are custom wheeled mobility devices essential for quality of life [4 & 9]. The CRT Service Delivery Process (SDP), which involves assessing needs, obtaining, and delivering

equipment, is complex and requires specialized expertise. While existing research primarily focuses on quantitatively assessing the effectiveness of the SDP, these approaches can overlook the nuanced, lived experiences of those navigating the system. The current process involves multiple stakeholders, including wheelchair users, clinicians, suppliers, manufacturers, and insurers, all of whom influence timelines and outcomes in various ways. Different challenges emerge once these stakeholders actively navigate the system [1]. Despite guidance provided by standard operating procedures, unexpected barriers continue to surface, complicating efforts to fully address wheelchair users' needs.

From a design research perspective, addressing these complexities requires a flexible, iterative approach. Unlike the structured methodologies typical of engineering, design prioritizes a deep understanding of user needs through primary research, followed by iterative cycles of ideation, prototyping, and refinement. By visualizing the lived experiences of stakeholders involved in the acquisition process, this study aims to identify opportunities for enhancing wheelchair user experiences and outcomes within the current service framework. Specifically, we use co-design approaches to address two core research questions:

- What does the existing CRT SDP look like from the perspectives of the various stakeholders?

- Should we focus on improving the implementation of the existing model or do we need to change the CRT SDP?

METHODS

This study was approved by The Ohio State University’s Institutional Review Board. Data were collected using a mixed-methods approach that combined semi-structured interviews and co-design workshops with various stakeholders, including wheelchair users, care providers, clinicians, and manufacturers. The semi-structured interviews incorporated a balance of open-ended and targeted questions, providing structure while allowing participants to share detailed personal perspectives [5]. This format facilitated nuanced insights into stakeholders' experiences, especially regarding wheelchair users’ experiences with wheelchair acquisition.

Informal interviews with various stakeholders such as wheelchair users, clinicians and insurers were conducted to gather insights into their experiences, identifying challenges in the current system and the impact of policy frameworks on the acquisition journey. The findings from these interviews informed the design of subsequent co-design workshops. The co-design workshops served as collaborative platforms, enabling participants from diverse fields to engage, exchange ideas, and collectively envision new possibilities and solutions [8]. Theseworkshops (see Table 1) involved a diverse range of stakeholders, including wheelchair users, care providers, clinicians, suppliers, manufacturers, and insurers, with a focus on human-centered design practices.

Table 1. All participants, who were recruited based on personal connections, participated in the workshops voluntarily with a small incentive.

|

Participant Role |

Wheelchair User |

Caregiver |

Clinician |

Manufacturer |

Insurer |

Supplier |

|

Qty |

3 |

3 |

3 (+3)* |

2 |

1 |

2 |

*Three of the workshop participants, who were caregivers, suppliers, and manufacturers, also had clinical backgrounds and chose to identify with the role of a clinician during some part of the workshop.

After informed consent was obtained, the participants were asked to engage in the following activities: first, verbally walking through and commenting on the existing RESNA Wheelchair Service Provision Guide; second, an Individual Experience Mapping [8] activity using pre-selected materials to plot positive and negative experiences along a timeline; and lastly, Collective Visioning [6] to elicit latent and tacit needs and dreams in order to facilitate their ability to envision optimistic future scenarios. These sessions provided a holistic view of stakeholder needs, surfacing multiple perspectives that are often overlooked in conventional design processes. By bringing together various stakeholders, the workshops facilitated shared insights and fostered a deeper understanding of each stakeholder's priorities, constraints, and aspirations.

The mixed-methods approach revealed preliminary findings on the challenges faced by wheelchair users within the current design, acquisition, and delivery systems, emphasizing the unmet need for processes that prioritize users' autonomy, social and emotional well-being, and long-term mobility needs. Data from the sessions were captured and organized using a Miro board (online whiteboard) to create a comprehensive data corpus for qualitative analysis.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was employed [2], combining inductive and deductive approaches to enhance the depth of analysis [7]. This process identified recurring themes within the data, providing a nuanced understanding of the stakeholders' experiences. A summary visualization was subsequently developed by synthesizing insights from all stakeholders into a unified, time-based map. This map highlights stakeholders’ expectations and aspirations for the future of the wheelchair acquisition process, emphasizing wheelchair users’ vision for improved SDP.

RESULTS

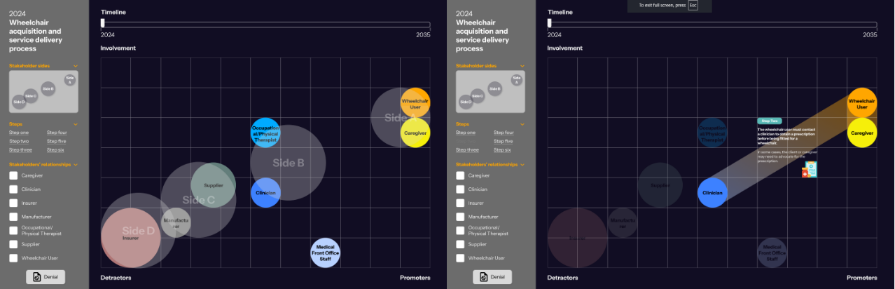

A total of 13 '2035 workflows' (see Figure 1) were created by the workshop participants (see Table 1), with one map developed collaboratively by two participants and the remaining 12 maps created individually. These workflows were initially compiled and organized into a draft static visualization, which later evolved into an interactive visual model (see Figure 2). The visualizations were reviewed and coded to align with the study’s findings and feedback from the research team. The model was further refined to emphasize the complexities of CRP SDP, illustrating the influences of various stakeholders, their interactions with one another and their impact on the process.

Interactive visual model

The lived experiences shared by stakeholders informed the development of an interactive visual model (see Figure 2) that captures the complexities of the system in greater depth than numeric and verbal descriptions alone [3]. This model integrates a time-based component to compare the current and idealized landscapes from the perspectives of the involved stakeholders. In this specific example shown in Figure 2, the visualizations developed through co-design workshops, depict the wheelchair users and caregivers’ experiences in ‘Side A’ within the current system (Figure 2, Left), where stakeholders are often perceived to work in silos rather than collaboratively navigating the process. In contrast, their aspirations for a more streamlined, user-centered future are illustrated (Figure 2, Right), emphasizing a vision where active collaboration among stakeholders is central to improving the system.

Using stakeholder influence map as the central visual element (see Figure 3), it becomes the second layer of visualizations to help identify who holds influence, how each stakeholders interact, and their potential impact on the outcome, aiding in decision-making and SDP. This specific figure explores the relationships and their interconnected roles within the system from the wheelchair users’ perspective. This visualization supported the creation of an interactive model that dynamically highlights relationships based on selected stakeholders, providing deeper insight into their roles within the CRT SDP.

DISCUSSION

Results from this research highlight the complexities of the current wheelchair SDP, which creates significant challenges for stakeholders, particularly wheelchair users, in receiving their chairs promptly. Key issues include navigating lengthy delivery timelines, with one caregiver (P5) noting, "It took almost three months for him to even get someone to come out and measure him," and challenges with insurance processes, as another caregiver (P8) shared, "…I would love if doctors told the insurance companies what the client needs, because right now it's vice versa…" Participants envision a more collaborative and streamlined system for 2035, with a wheelchair user (P2) expressing the need for a process "done with me" rather than "done to me."

Based on participants’ visions for their ideal wheelchair acquisition experiences in 2035, the development of the interactive visual model serves as a crucial tool for visualizing the challenges and complexities within the current wheelchair SDP. By highlighting existing gaps and potential opportunities, the prototype reveals areas that require closer attention to improve wheelchair users’ experiences. The incorporation of a time-based element, derived from the insights gathered during the co-design sessions, not only captured present-day challenges but also projected future scenarios. This approach offers a dynamic method to evaluate questions such as: “Are we meeting the needs of our users in a timely manner?”, “Are we allocating resources effectively in areas that require more support?”, and “How close are we to achieving a truly user-centered system?”

Furthermore, by using lived experiences as a benchmark, the interactive model's narrative-based and time-based features provide a framework for measuring progress toward stakeholders’ goals. This visualization captures overlapping participant narratives, reflecting the preliminary stages of analysis of this research. As additional stakeholders are engaged, the scope of insights will expand, enabling a more comprehensive identification of changes needed to address diverse needs and perspectives effectively. In addition, the results do emphasize the need to reassess the implementation of the current wheelchair SDP, where the implementation could better align the system with varying needs of all involved stakeholders. By adjusting the way services are delivered, stakeholders can address critical issues more efficiently, improving the overall motivation and experience for people navigating the system.

CONCLUSIONS

This research highlights how a design approach of visualizing stakeholder relationships over time can clarify the complexities of CRT SDP and inspire future visions. By leveraging co-design, we created a dynamic model that not only maps current challenges but also projects an ideal system for 2035. This approach offers a fresh and novel perspective, emphasizing targeted refinements over systemic overhaul to better align services with stakeholder needs. Future work should continue to explore strategies to foster more responsive and inclusive healthcare solutions.

REFERENCES

Journal articles:

[1] Burrola-Mendez, Y., Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Goldberg, M., & Pearlman, J. (2019). Comparing the effectiveness of a hybrid and in-person courses of wheelchair service provision knowledge: A controlled quasi-experimental study in India and Mexico. PloS one, 14(5), e0217872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217872

[2] Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),77–101. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

[3] O'Connor, S., Waite, M., Duce, D., O'Donnell, A., & Ronquillo, C. (2020). Data visualization in health care: The Florence effect. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1488–1490. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14334

[4] Taylor, D. M. (2018). Americans With Disabilities: 2014. United State Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce, 70–152. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p70-152.pdf

[5] Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Sarib, M., Alhabsyi, F., & Syam, H. (2022). Semi-structured interview: A methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. Ruslin, 12, 22-29.

[6] Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

[7] Proudfoot, K. (2023). Inductive/Deductive Hybrid Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 17(3), 308-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898221126816

Book:

[8] Sanders, E. B. N., & Stappers, P. J. (2012). Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. BIS Publishers.

Website:

[9] Guidelines on the Provision of Manual Wheelchairs in Less Resourced Settings. (2008). World Health Organization.